Maldi Method to Characterize a Specific Protein Reviews

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a diagnostic tool in human and veterinarian helminthology: a systematic review

Parasites & Vectors volume 12, Commodity number:245 (2019) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) has become a widely used technique for the rapid and accurate identification of bacteria, mycobacteria and certain fungal pathogens in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Thus far, only few attempts take been fabricated to apply the technique in clinical parasitology, particularly regarding helminth identification.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the scientific literature on studies pertaining to MALDI-TOF MS as a diagnostic technique for helminths (cestodes, nematodes and trematodes) of medical and veterinary importance. Readily available electronic databases (i.eastward. PubMed/MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Library, Spider web of Science and Google Scholar) were searched from inception to 10 Oct 2018, without restriction on year of publication or language. The titles and abstracts of studies were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers. Relevant articles were read in total and included in the systematic review.

Results

A total of 84 peer-reviewed articles were considered for the terminal analysis. Near papers reported on the application of MALDI-TOF for the study of Caenorhabditis elegans, and the technique was primarily used for identification of specific proteins rather than entire pathogens. Since 2015, a minor number of studies documented the successful apply of MALDI-TOF MS for species-specific identification of nematodes of homo and veterinary importance, such as Trichinella spp. and Dirofilaria spp. However, the quality of available information and the number of examined helminth samples was low.

Conclusions

Data on the use of MALDI-TOF MS for the diagnosis of helminths are scarce, merely recent evidence suggests a potential office for a reliable identification of nematodes. Time to come research should explore the diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF MS for identification of (i) adult helminths, larvae and eggs shed in faecal samples; and (ii) helminth-related proteins that are detectable in serum or body fluids of infected individuals.

Groundwork

In clinical and laboratory diagnostic settings, mass spectrometry (MS) has been utilized for several decades equally an arroyo for protein-centred analysis of samples in medical chemical science [1, 2] and haematology laboratories [iii]. In 1975, Anhalt & Fenselau [4] proposed, for the first time, the modification of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization fourth dimension-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS as a method to characterize bacteria. Indeed, it was demonstrated that unlike bacterial species show specific poly peptide mass spectra, which can be used for rapid identification.

During the past decade, MALDI-TOF MS has been widely introduced every bit a diagnostic technique in microbiology laboratories, where information technology has replaced nigh other tools (due east.g. phenotypic tests, biochemical identification and agglutination kits) as the starting time-line pathogen identification method due to its high diagnostic accuracy, robustness, reliability and rapid turn-around time [five]. MALDI-TOF MS is at present routinely employed for identification of bacteria [5,vi,7,8], mycobacteria [5, 9] and some fungi [eight]. More recently, MALDI-TOF MS has been practical in research settings for the detection and identification of viruses [ten], protozoans and arthropods [11, 12]. In clinical practice, a specific quantity is brought on a target plate (east.g. culture-grown pathogen). Side by side, the target plate is pre-treated with a chemical reagent (and so-called matrix, e.grand. α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) and subjected to a mass spectrometer for further assay. The MALDI-TOF apparatus, which is commercially bachelor through dissimilar manufacturers [thirteen, 14], uses laser to disperse and ionize the analyte into different molecules, which motion through a vacuum driven by an electric field before reaching a detector membrane. The fourth dimension-of-flight of the various molecules depends on their mass and their electrical charge. The specific time-of-flying data are assembled, resulting in specific spectra that are compared to a commercial database, which allows for a rapid identification of the infectious agent and diagnostic accurateness, the latter of which is commonly expressed as a score.

MALDI-TOF MS has several strengths if compared to other diagnostic tools, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. Once the mass spectrometer and the respective databases are available in a laboratory, individual pathogen identification is cheap, and the sample grooming procedure does neither require highly skilled technicians nor complex additional laboratory infrastructure. Of note, MALDI-TOF MS is considerably less prone to contamination and results are bachelor within a few minutes. However, constant ability supply is a prerequisite, which limits the suitability of the technique in resources-constrained settings. Yet, information technology should exist noted that MALDI-TOF MS is no longer restricted to high-income countries as it is increasingly available in reference laboratories in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere [xv,16,17,18,19].

MALDI-TOF does not e'er require culture-grown colonies of a given pathogen. Instead, information technology can also be employed to identify microorganisms direct from positive blood civilization broths [6] with high diagnostic accuracy [7]. Recently, Yang et al. [xx] proposed a new framework to analyse MALDI-TOF spectra of bacterial mixtures (instead of but a single pathogen) and to directly characterize each component without purification procedures. Hence, this procedure might become available to be employed straight on other torso fluids (e.g. urine, respiratory specimens and faecal samples), which would further increment its relevance in clinical practice [21, 22].

In contrast to clinical bacteriology, little research has been carried out pertaining to the application of MALDI-TOF MS for identification of parasites of human or veterinary importance [23]. Several studies utilized the technique on protozoan parasites such as Leishmania spp. [24,25,26], Giardia spp. [27], Cryptosporidium spp. [28], Trypanosoma spp. [29], Plasmodium spp. [xxx,31,32] and Dientamoeba spp. [33]. These studies used pre-treatment with ethanol and acetonitrile before subjecting the whole pathogens to MALDI-TOF assay. Additionally, the technique has been used for identification of ectoparasites and vectors, such as ticks [34,35,36,37], fleas [38,39,40,41] and mosquitoes [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. In contrast to the experiments on protozoans, only selected parts of the ectoparasites and vectors (e.g. legs, thoraxes or wings) were used and subjected to the aforementioned extraction method. A farther novel approach to apply MALDI-TOF MS in clinical parasitology is the identification of specific serum peptides that are detectable in parasite-infected individuals [50].

Helminth infections caused past nematodes (e.g. Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworm, Strongyloides stercoralis and Trichuris trichiura), cestodes (e.chiliad. Taenia spp.) and trematodes (e.k. Fasciola spp. and Schistosoma spp.) account for a considerable global burden of disease and are among the virtually mutual infections in marginalized populations in the tropics and subtropics [51]. Indeed, according to estimates put forth past the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, 3.35 million disability-adapted life years (DALYs) were attributable to intestinal nematode infections and schistosomiasis in 2017 [52].

Diagnosis is pivotal for constructive treatment but requires at to the lowest degree a basic laboratory infrastructure, light microscopes and well-trained laboratory technicians who might not exist available in remote areas of tropical and subtropical countries. In loftier-resource settings, in contrast, cognition on microscopic identification of helminths is waning in many laboratories. Information technology is surprising that the potential applicability of MALDI-TOF MS equally a diagnostic tool for helminths of homo and veterinary importance has not yet been systematically assessed, in particular considering the technique has been successfully employed for identification of nematode institute pathogens [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Hence, the goal of this systematic review was to summarize the bachelor information on MALDI-TOF MS awarding for diagnosis of helminths of medical and veterinary importance, and to provide recommendations for future enquiry needs.

Methods

Search strategy

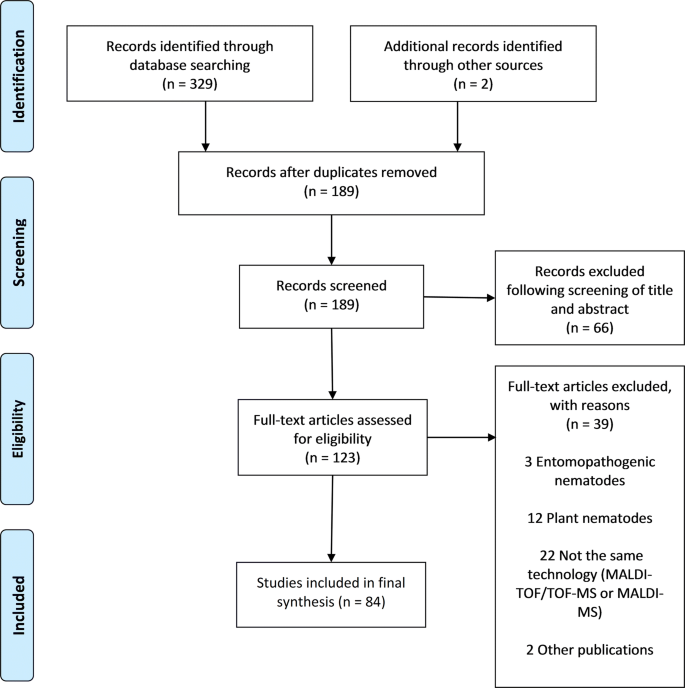

A systematic literature review was performed to identify all relevant scientific studies pertaining to MALDI-TOF MS every bit a diagnostic identification technique in medical and/or veterinary helminthology. The inquiry was performed co-ordinate to the guidance expressed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [59].

The following electronic databases were systematically searched: MEDLINE/PubMed, ScienceDirect-Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Google Scholar. All studies published from inception to x Oct 2018 were eligible for inclusion without linguistic communication restrictions. The bibliographies of all eligible documents were hand-searched for additional references. Conference abstracts or book capacity detected through these databases and additional library searches were also considered. The search strategy comprised keywords related to the MALDI-TOF MS technique (e.one thousand. "MALDI-TOF" and "matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption/ionization fourth dimension-of-flying") and helminthology (e.g. "helminth", "nematode", "cestode" and "trematode"). The full search strategies for every database are provided in Additional file 1 and the PRISMA checklist in Additional file ii.

Eligibility screening

After the systematic literature search, all duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies were screened to identify manuscripts relevant to the inquiry question. Scientific reports on helminths of either plants or insects as well as studies on symbiotic bacteria of helminths were excluded for this review. However, we kept all publications related to the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, every bit it is used as a model organism for biomedical research. Additionally, studies pertaining to MALDI-TOF/TOF tandem MS were excluded, as this is a unlike modification of the MALDI-TOF MS technique, which is not routinely employed in clinical microbiology laboratories, merely rather in research laboratory use for accurate characterization or sequencing of components similar amino acids, metabolites, saccharides, etc. [lx,61,62].

Data extraction and assay

The literature search was performed past the commencement author of this manuscript (MF). All titles and abstracts were so independently reviewed past the first and the final writer (MF and SLB) for inclusion and any disagreement was discussed until consensus was reached. All extracted manuscripts were analysed using a reference director software (Mendeley; http://world wide web.mendeley.com).

Results

Search results, number and year of publication of eligible studies

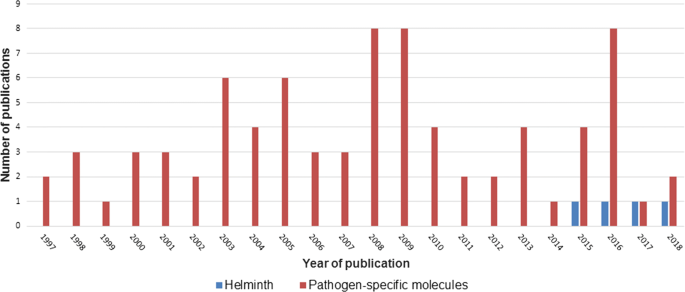

The search procedure and results obtained are shown in Fig. i. In brief, the initial literature search yielded 329 published studies, with an additional two abstracts identified through further search. Following removal of 142 duplicates, a total of 189 articles were assessed in more detail, of which 66 studies were excluded based on the analysis of the respective titles and abstracts. A total-text assay was carried out on the remaining 123 studies; 39 articles were finally excluded because their telescopic was outside the current enquiry question. Hence, 84 articles were included, and these were published between 1997 and 2018. Figure ii shows the number of publications, stratified past year of publication. The heterogeneity of data reported in the articles precluded any meaningful meta-assay (Additional file 3).

PRISMA diagram for a systematic review examining the application of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry equally potential tool in diagnostic man and veterinary helminthology

Publications in the peer-reviewed literature pertaining to the application of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for identification of helminths or specific pathogen-related components, as revealed past a systematic review, stratified by yr of publication

Specific applications of MALDI-TOF MS

The first two manuscripts published in 1997 described structural analyses of glycosphingolipids found in Ascaris suum and C. elegans [63, 64]. Indeed, 95% of all eligible studies used MALDI-TOF MS for identification of specific components rather than for the identification of entire pathogens (Fig. 2). It was only in 2015 when a written report on MALDI-TOF MS equally diagnostic tool for direct identification of Dirofilaria spp. became bachelor [65]. Presently thereafter followed a proof-of-concept study utilizing MALDI-TOF MS for identification and differentiation of Trichinella spp. and some narrative reviews mentioning the lack of information on MALDI-TOF in helminthology [32, 66, 67]. Still, most studies focused on distinct analyses of specific components, such as peptides [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,eighty,81,82,83,84,85,86], proteins [69, 87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114], lipids [61, 62, 115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124], carbohydrates [125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143] and nucleic acids [144] in a research context. Hence, MALDI-TOF was mainly applied to study and compare the proteome or the peptidome of dissimilar helminth species, and almost reports focused on C. elegans. For example, Husson et al. [74] employed a new approach combining liquid chromatography with MALDI-TOF MS to map and differentiate the neuropeptide profiles of C. elegans and the closely related species C. briggsae.

The ii studies aiming at an identification of entire pathogens provided prove that MALDI-TOF MS could reliably differentiate between species inside the genus Trichinella [67] and Dirofilaria [65], respectively. In the study by Mayer-Scholl et al. [67], nine species and three genotypes of Trichinella isolated from mice, domestic pigs, wild boars and guinea pigs were utilized to create an in-house database with 27 raw spectra generated per specimen. All tested isolates could be distinguished with high diagnostic accuracy. The report by Pshenichnaya et al. [65], which had simply been published as a conference abstract, investigated five Dirofilaria repens and five D. immitis specimens, the causative agents of human and veterinary dirofilariasis, and reported that these could exist well differentiated by MALDI-TOF MS. However, information were express regarding the origin of the written report samples, the quality of the spectra obtained by MALDI-TOF and the repeatability of the results. Notwithstanding, during the revision of this systematic review, Pshenichnaya et al. [145] published their work on dirofilariasis in a peer-reviewed periodical and provided too data for ii dissimilar species of Ascaris (i.eastward. A. suum and A. lumbricoides). These helminths could be differentiated past MALDI-TOF based on specific peaks and protein spectra patterns later a cell lysis using the Sepsityper Kit 50 (Bruker Daltonics; Bremen, Federal republic of germany) and a poly peptide extraction with seventy% formic acid and acetonitrile. However, this study has several limitations, and it remains unclear whether calibration steps or assessments of the repeatability and reproducibility of the analyses were performed. An additional newspaper, published in 2017, reported on MALDI-TOF MS application for cyathostomin helminths, a very diverse group of intestinal parasites infecting horses [66]. These so-called "small strongyles" bear witness a high degree of resistance against benzimidazole anthelminthics and may lead to astringent equine enteropathy, colic and decease [146]. The study examined several species belonging to the cyathostomin helminths (e.g. Coronocyclus coronatus, C. labiatus and C. labratus) and establish distinct protein spectra among developed helminths of dissimilar species [66]. These findings were recently confirmed and substantiated past another study on the application of MALDI-TOF for differentiation of cyathostomins, which was published in April 2019 [147].

Discussion

We systematically reviewed the available literature pertaining to the application of MALDI-TOF MS for identification of helminthic pathogens of human and veterinary importance. While the technique has been successfully employed for many major classes of pathogens (eastward.grand. bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi), information on its utilise in diagnostic helminthology are scarce. Several studies reported on the differential assay of specific components, such as proteins, peptides or lipids with MALDI-TOF MS techniques, but only ii recent manuscripts and one conference abstract provided 'proof-of-concept' evidence of its potential utility in diagnosing and differentiating helminth species of medical or veterinarian relevance.

The majority of articles identified in this systematic review focused on poly peptide-centred analyses of helminth samples. It is of import to mention that some of the MALDI-TOF MS devices employed in these studies had been subjected to modifications that are not commonly available in routine clinical laboratories. Additionally, these experiments frequently employed a circuitous sample pre-handling comprising a protein separation past high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) or electrophoresis. Yet, some recent proof-of-concept studies take shown that MALDI-TOF MS is also capable of diagnosing entire helminthic pathogens and differentiating similar species within the same genus based on an analysis of their individual poly peptide spectra [66, 67]. Considering no helminths are currently included in commercially bachelor MALDI-TOF MS identification databases, private in-house databases need to exist created through generation of primary spectra libraries, ideally post-obit established guidelines and protocols that are similar to those employed past the manufacturers of commercially available mass spectrometers [148]. Indeed, previous studies have described the sensitive, reliable and highly reproducible identification of helminths that crusade plant infections and have ended that MALDI-TOF MS should be more than widely employed as a 'rapid detection tool' [54,55,56,57,58]. Ahmad et al. [56], for example, reported on the suitability of MALDI-TOF MS to differentiate harmless and juvenile infective stages of single plant nematodes, as these showed unique, characteristic poly peptide peak patterns. These studies should be considered equally relevant because constitute-parasitic nematodes can sometimes also be found in human stool samples [149, 150]. In Brazil, for example, eggs of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne spp. were detected in human faeces using a microscopic sedimentation method [151]. Future studies should likewise employ MALDI-TOF on serum, equally a recent written report reported the detection of specific proteins in serum of mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum [50].

While helminth infections pose a considerable brunt on human and beast health [152], an accurate diagnosis of these conditions is frequently challenging. Indeed, elementary diagnostic tools such equally stool microscopy for soil-transmitted helminth infections are of express value if the infection intensity is depression and highly sensitive diagnostic techniques such equally PCR-based assays are only available in selected reference laboratories exterior endemic areas [153]. In loftier-income countries, in dissimilarity, knowledge regarding standard diagnostic parasitology is waning and differentiation of closely related helminth species based on their microscopic morphology requires skilled laboratory technicians [154]. Moreover, some infections cannot be reliably distinguished with standard diagnostic techniques. A prominent example are infections caused past cestodes of the genus Taenia [155], which may cause a relatively harmless intestinal infection if cysts of Taenia saginata or T. solium are orally ingested with meat of cattle or pig. While eggs of T. saginata are not infectious to humans, T. solium eggs can atomic number 82 to the potentially fatal disease (neuro-)cysticercosis. While the correct diagnosis has important implications for handling, patient direction and potential contact screening (intestinal carriage of adult T. solium worms poses an increased risk of cysticercosis for close contacts, such every bit family members), it is incommunicable to distinguish both species based on the identical morphology of their eggs under a microscope. Molecular tools can reach an accurate differentiation of the ii species, but are only available in research settings [155,156,157]. Sometimes, proglottids of adult worms are also passed in the faeces. While a distinct differentiation is possible based on the uterine branches within a proglottid, misidentification using this approach has been reported in clinical practise [158]. Hence, achieving a species-specific differentiation based on MALDI-TOF MS would contribute to an enhanced, more reliable identification, and time to come studies should thus accost this issue. Like considerations hold also true for other infective agents that tin hardly be differentiated by other methods (due east.g. different Echinococcus species), novel species (e.g. hybrid species of Schistosoma spp., which accept recently been reported from Corsica, France [159]) and notoriously difficult-to-detect infections (east.g. strongyloidiasis). An overview of pathogens for which evolution of MALDI-TOF MS identification protocols would appear particularly promising is summarized in Table 1.

Information technology is important to consider the fixative in which a parasitological sample is stored. Both formaldehyde and ethanol are commonly used to enable a long-term storage of biological specimens, just this may lead to profound changes of the protein structure [160], which is likely to influence on the results of MALDI-TOF examinations carried out on such samples. The virtual impossibility to dilate nucleic acids from formaldehyde-containing solutions [161] due to fragmentation of the single components [162] renders most PCR tests useless on these sample types, but MALDI-TOF analyses of protein spectra might still be possible, albeit with different spectra if compared to native samples. Hence, futurity studies should evaluate this technique on different kinds of fixatives and on samples that take been stored for prolonged periods.

The present review identified only a few successful studies that employed MALDI-TOF MS to diagnose helminths. Limitations include the complicated pre-treatment procedures employed in some studies and the rather incomplete data presentation in one of the more than clinically oriented research projects [65]. New research is needed to determine whether this technique might become a clinically meaningful addendum to the current prepare of diagnostic options. However, experiences made in clinical bacteriology, mycobacteriology, mycology every bit well as with ectoparasites (east.thou. ticks) and vectors (e.g. mosquitoes) [12, 37, 163] are promising. Whereas MALDI-TOF MS is mainly used on civilisation-grown colonies for identification of bacteria and mycobacteria, the goal in helminthology will be to provide a species-specific diagnosis based on either macroscopic elements or eggs and larvae that are present in stool samples (or other trunk fluids and tissue samples). Hence, specific protocols will need to be elaborated to this end, which may include sample preparation, purification and concentration steps, including guidance on the near advisable sample preservation. Withal, such protocols accept been successfully developed in the by (e.1000. for identification of mycobacteria or moulds) [164, 165]. More recently, specific pre-treatment modifications take even immune to utilise MALDI-TOF MS on blood culture broths [166] and fresh urine samples for straight identification of bacteria [167]. Additionally, detection of parasites in circuitous samples (e.g. claret), should be considered (e.g. as an antigen exam for Wuchereria bancrofti [168] or for the detection of specific serum peptides [169]).

Yet, much research and rigorous validation is nonetheless needed before MALDI-TOF MS might be employed directly on stool samples, and priority should thus exist given to (i) the institution of in-house main spectra library databases to allow for species-specific identification of selected helminths; (ii) the subsequent development of sample treatment protocols; (3) the validation of this technique on different clinical sample types; and (iv) the elaboration of MALDI-TOF MS to be employed on fixed samples.

Conclusions

The present systematic review elucidated that MALDI-TOF MS, which is at present routinely used in many clinical microbiology laboratories for identification of bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria, could potentially also be employed in the context of helminth diagnosis. Preliminary data propose that MALDI-TOF MS might hold promise as a futurity diagnostic tool for direct and rapid identification of pathogenic helminths in clinical samples with sufficient diagnostic accuracy. Further studies are needed to evaluate these concepts and to develop specific databases for helminth identification, followed by rigorous validation on well characterised clinical specimens.

Availability of data and materials

The search strategy and all manuscripts included in this systematic review are available inside the article and its boosted files.

Abbreviations

- DALY:

-

disability-adjusted life twelvemonth

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Affliction (Report)

- MALDI-TOF:

-

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- MS:

-

mass spectrometry

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

-

Tanaka K, Waki H, Ido Y, Akita Due south, Yoshida Y, Yoshida T, et al. Poly peptide and polymer analyses up to thousand/z 100 000 by light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation ionization fourth dimension-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1988;2:151–3.

-

Marvin LF, Roberts MA, Fay LB. Matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry in clinical chemistry. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;337:11–21.

-

Rees-Unwin KS, Morgan GJ, Davies Iron. Proteomics and the haematologist. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26:77–86.

-

Anhalt JP, Fenselau C. Identification of bacteria using mass spectrometry techniques. Anal Chem. 1975;47:219–25.

-

Clark AE, Kaleta EJ, Arora A, Wolk DM. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry: a primal shift in the routine do of clinical microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:547–603.

-

Carbonnelle Due east, Mesquita C, Bille E, Mean solar day Due north, Dauphin B, Beretti JL, et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry tools for bacterial identification in clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:104–9.

-

Singhal Northward, Kumar 1000, Kanaujia PK, Virdi JS. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: an emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Forepart Microbiol. 2015;half dozen:791.

-

Angeletti Southward. Matrix assisted laser desorption fourth dimension of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) in clinical microbiology. J Microbiol Methods. 2017;138:twenty–nine.

-

El Khéchine A, Couderc C, Flaudrops C, Raoult D, Drancourt Yard. Matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization fourth dimension-of-flight mass spectrometry identification of mycobacteria in routine clinical practise. PLoS I. 2011;half-dozen:e24720.

-

Sjöholm MIL, Dillner J, Carlson J. Multiplex detection of homo herpesviruses from archival specimens by using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:540–v.

-

Yssouf A, Almeras L, Raoult D, Parola P. Emerging tools for identification of arthropod vectors. Future Microbiol. 2016;xi:549–66.

-

Vega-Rúa A, Pagès N, Fontaine A, Nuccio C, Hery 50, Goindin D, et al. Comeback of musquito identification by MALDI-TOF MS biotyping using protein signatures from ii trunk parts. Parasit Vectors. 2018;xi:574.

-

Faron ML, Buchan BW, Hyke J, Madisen Due north, Lillie JL, Granato PA, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the Bruker MALDI Biotyper CA Organisation for the identification of clinical aerobic gram-negative bacterial isolates. PLoS 1. 2015;10:e0141350.

-

Luo Y, Siu GKH, Yeung ASF, Chen JHK, Ho PL, Leung KW, et al. Performance of the VITEK MS matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flight mass spectrometry organisation for rapid bacterial identification in ii diagnostic centres in Mainland china. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:eighteen–24.

-

Fall B, Lo CI, Samb-Ba B, Perrot N, Diawara Due south, Gueye MW, et al. The ongoing revolution of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for microbiology reaches tropical Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:641–7.

-

Lo CI, Autumn B, Sambe-Ba B, Flaudrops C, Faye Northward, Mediannikov O, et al. Value of matrix assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-time of flying (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Africa and tropical areas. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017;11:1360–seventy.

-

Diongue K, Kébé O, Faye MD, Samb D, Diallo MA, Ndiaye M, et al. MALDI-TOF MS identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with pityriasis versicolor at the Seafarers' Medical Service in Dakar, Senegal. J Mycol Med. 2018;28:590–3.

-

Taverna CG, Mazza M, Bueno NS, Alvarez C, Amigot South, Andreani M, et al. Development and validation of an extended database for yeast identification by MALDI-TOF MS in Argentine republic. Med Mycol. 2019;57:215–25.

-

Chabriere E, Bassène H, Drancourt Thousand, Sokhna C. MALDI-TOF-MS and point of care are disruptive diagnostic tools in Africa. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;26:S83–8.

-

Yang Y, Lin Y, Qiao L. Direct MALDI-TOF MS identification of bacterial mixtures. Anal Chem. 2018;90:10400–8.

-

Ferreira Fifty, Sánchez-Juanes F, González-Avila M, Cembrero-Fuciños D, Herrero-Hernández A, González-Buitrago JM, et al. Directly identification of urinary tract pathogens from urine samples by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2110–v.

-

Íñigo M, Coello A, Fernández-Rivas Thousand, Rivaya B, Hidalgo J, Quesada Medico, et al. Direct identification of urinary tract pathogens from urine samples, combining urine screening methods and matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-time of flying mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:988–93.

-

Singhal N, Kumar M, Virdi JS. MALDI-TOF MS in clinical parasitology: applications, constraints and prospects. Parasitology. 2016;143:1491–500.

-

Cassagne C, Pratlong F, Jeddi F, Benikhlef R, Aoun K, Normand A-C, et al. Identification of Leishmania at the species level with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;twenty:551–vii.

-

Culha G, Akyar I, Yildiz Zeyrek F, Kurt Ö, Gündüz C, Özensoy Töz Southward, et al. Leishmaniasis in Turkey: determination of Leishmania species by matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization fourth dimension-of-flying mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Islamic republic of iran J Parasitol. 2014;ix:239–48.

-

Lachaud L, Fernández-Arévalo A, Normand AC, Lami P, Nabet C, Donnadieu JL, et al. Identification of Leishmania by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry using a free web-based application and a dedicated mass spectral library. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2914–33.

-

Villegas EN, Glassmeyer ST, Ware MW, Hayes SL, Schaeffer FW. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flying mass spectrometry-based assay of Giardia lamblia and Giardia muris. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2006;53:S179–81.

-

Magnuson ML, Owens JH, Kelty CA. Characterization of Cryptosporidium parvum by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4720–iv.

-

Avila CC, Almeida FG, Palmisano Grand. Direct identification of trypanosomatids by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flying mass spectrometry (DIT MALDI-TOF MS). J Mass Spectrom. 2016;51:549–57.

-

Marks F, Meyer CG, Sievertsen J, Timmann C, Evans J, Horstmann RD, et al. Genotyping of Plasmodium falciparum pyrimethamine resistance by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flying mass spectrometry. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:466–72.

-

Gitau EN, Kokwaro Go, Newton CR, Ward SA. Global proteomic analysis of plasma from mice infected with Plasmodium berghei ANKA using two dimensional gel electrophoresis and matrix assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flying mass spectrometry. Malar J. 2011;10:205.

-

de Dios Caballero J, Martin O. Application of MALDI-TOF in parasitology. In: Cobo F, editor. The utilise of mass spectrometry technology (MALDI-TOF) in clinical microbiology. London: Elsevier Inc.; 2018. p. 235–53.

-

Calderaro A, Buttrini M, Montecchini S, Rossi S, Piccolo Yard, Arcangeletti MC, et al. MALDI-TOF MS equally a new tool for the identification of Dientamoeba fragilis. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:xi.

-

Karger A, Kampen H, Bettin B, Dautel H, Ziller Thousand, Hoffmann B, et al. Species conclusion and characterization of developmental stages of ticks by whole-fauna matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;3:78–89.

-

Yssouf A, Flaudrops C, Drali R, Kernif T, Socolovschi C, Berenger JM, et al. Matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flight mass spectrometry for rapid identification of tick vectors. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:522–eight.

-

Diarra AZ, Almeras L, Laroche M, Berenger J-Yard, Koné AK, Bocoum Z, et al. Molecular and MALDI-TOF identification of ticks and tick-associated bacteria in Republic of mali. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005762.

-

Dib L, Benakhla A, Raoult D, Parola P. MALDI-TOF MS identification of ticks of domestic and wild animals in Algeria and molecular detection of associated microorganisms. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;57:39–49.

-

Dvorak Five, Halada P, Hlavackova K, Dokianakis E, Antoniou M, Volf P. Identification of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flying mass spectrometry. Parasit Vectors. 2014;vii:21.

-

Yssouf A, Socolovschi C, Leulmi H, Kernif T, Bitam I, Audoly K, et al. Identification of flea species using MALDI-TOF/MS. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;37:153–7.

-

Lafri I, Almeras Fifty, Bitam I, Caputo A, Yssouf A, Forestier C-Fifty, et al. Identification of Algerian field-caught phlebotomine sand wing vectors past MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004351.

-

El Hamzaoui B, Laroche M, Almeras L, Bérenger J-1000, Raoult D, Parola P. Detection of Bartonella spp. in fleas by MALDI-TOF MS. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006189.

-

Dieme C, Yssouf A, Vega-Rúa A, Berenger JM, Failloux AB, Raoult D, et al. Accurate identification of Culicidae at aquatic developmental stages by MALDI-TOF MS profiling. Parasit Vectors. 2014;vii:544.

-

Yssouf A, Parola P, Lindström A, Lilja T, L'Ambert G, Bondesson U, et al. Identification of European mosquito species past MALDI-TOF MS. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2375–8.

-

Niare S, Berenger J-K, Dieme C, Doumbo O, Raoult D, Parola P, et al. Identification of claret meal sources in the main African malaria mosquito vector by MALDI-TOF MS. Malar J. 2016;fifteen:87.

-

Tandina F, Almeras 50, Koné AK, Doumbo OK, Raoult D, Parola P. Use of MALDI-TOF MS and culturomics to identify mosquitoes and their midgut microbiota. Parasit Vectors. 2016;nine:495.

-

Raharimalala FN, Andrianinarivomanana TM, Rakotondrasoa A, Collard JM, Boyer South. Usefulness and accurateness of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a supplementary tool to identify mosquito vector species and to invest in development of international database. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:289–98.

-

Tahir D, Almeras L, Varloud Yard, Raoult D, Davoust B, Parola P. Assessment of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for filariae detection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;eleven:e0006093.

-

Niare Southward, Tandina F, Davoust B, Doumbo O, Raoult D, Parola P, et al. Accurate identification of Anopheles gambiae Giles trophic preferences past MALDI-TOF MS. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;63:410–9.

-

Tandina F, Laroche One thousand, Davoust B, Doumbo OK, Parola P. Blood meal identification in the cryptic species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii using MALDI-TOF MS. Parasite. 2018;25:forty.

-

Huang Y, Li W, Liu K, Xiong C, Cao P, Tao J. New detection method in experimental mice for schistosomiasis: ClinProTool and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization fourth dimension-of-flight mass spectrometry. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:4173–81.

-

Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the dandy neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1311–21.

-

GBD 2017 DALYs, Unhurt Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1859–922.

-

Calvo Due east, Flores-Romero P, López JA, Navas A. Identification of proteins expressing differences amidst isolates of Meloidogyne spp. (Nematoda: Meloidogynidae) by nano-liquid chromatography coupled to ion-trap mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1017–21.

-

Perera MR, Vanstone VA, Jones MGK. A novel approach to identify plant parasitic nematodes using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flying mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;nineteen:1454–60.

-

Ahmad F, Babalola OO, Tak HI. Potential of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a rapid detection technique in plant pathology: identification of plant-associated microorganisms. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:1247–55.

-

Ahmad F, Gopal J, Wu H. Rapid and highly sensitive detection of single nematode via direct MALDI mass spectrometry. Talanta. 2012;93:182–v.

-

Ahmad F, Babalola OO. Application of mass spectrometry every bit rapid detection tool in plant nematology. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2014;49:i–10.

-

Ahmad F, Babalola OO, Wu H-F. Potential of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a detection tool to identify plant-parasitic nematodes. J Nematol. 2014;46:132.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

-

Yergey AL, Coorssen JR, Backlund PS, Blank PS, Humphrey GA, Zimmerberg J, et al. De novo sequencing of peptides using MALDI/TOF-TOF. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:784–91.

-

Rush MD, Rue EA, Wong A, Kowalski P, Glinski JA, van Breemen RB. Rapid determination of procyanidins using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:11355–61.

-

Zhan 50, Xie Ten, Li Y, Liu H, Xiong C, Nie Z. Differentiation and relative quantitation of disaccharide isomers by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2018;90:1525–xxx.

-

Gerdt S, Lochnit G, Dennis RD, Geyer R. Isolation and structural analysis of 3 neutral glycosphingolipids from a mixed population of Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematoda: Rhabditida). Glycobiology. 1997;seven:265–75.

-

Lochnit G, Dennis RD, Zähringer U, Geyer R. Structural analysis of neutral glycosphingolipids from Ascaris suum adults (Nematoda: Ascaridida). Glycoconj J. 1997;fourteen:389–99.

-

Pshenichnaya N, Nagorny S, Aleshukina A, Ermakova L, Krivorotova E. Newspaper Poster Session II MALDI-TOF application of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry for the identification of dirofilariasis species. 2015. In: Poster presentation at the 25th European Briefing on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Copenhagen, Denmark on 26 April 2015. https://www.escmid.org/escmid_publications/escmid_elibrary/cloth/?mid=22817. Accessed 14 May 2019.

-

Bredtmann CM, Krücken J, Murugaiyan J, Kuzmina T, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Nematode species identification—current status, challenges and future perspectives for Cyathostomins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:283.

-

Mayer-Scholl A, Murugaiyan J, Neumann J, Bahn P, Reckinger S, Nöckler G. Rapid identification of the foodborne pathogen Trichinella spp. by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2016;xi:e0152062.

-

Marks NJ, Maule AG, Geary TG, Thompson DP, Li C, Halton DW, et al. KSAYMRFamide (PF3/AF8) is present in the gratis-living nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:422–5.

-

Kaji H, Tsuji T, Mawuenyega KG, Wakamiya A, Taoka M, Isobe T. Profiling of Caenorhabditis elegans proteins using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1755–65.

-

Husson SJ, Clynen E, Baggerman 1000, Janssen T, Schoofs L. Defective processing of neuropeptide precursors in Caenorhabditis elegans lacking proprotein convertase 2 (KPC-2/EGL-3): mutant analysis past mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1999–2012.

-

Ghaleb AM, Atwood J, Morales-Montor J, Damian RT. A 3 kDa peptide is involved in the chemoattraction in vitro of the male Schistosoma mansoni to the female person. Microbes Infect. 2006;viii:2367–75.

-

Yew JY, Davis R, Dikler Due south, Nanda J, Reinders B, Stretton AO. Peptide products of the afp-6 gene of the nematode Ascaris suum have different biological actions. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:872–82.

-

Nagano I, Wu Z, Takahashi Y. Functional genes and proteins of Trichinella spp. Parasitol Res. 2009;104:197–207.

-

Husson SJ, Landuyt B, Nys T, Baggerman G, Boonen K, Clynen E, et al. Comparative peptidomics of Caenorhabditis elegans versus C. briggsae by LC-MALDI-TOF MS. Peptides. 2009;30:449–57.

-

Weinkopff T, Atwood JA, Punkosdy GA, Moss D, Weatherly DB, Orlando R, et al. Identification of antigenic Brugia developed worm proteins past peptide mass fingerprinting. J Parasitol. 2009;95:1429–35.

-

Husson SJ, Clynen E, Boonen G, Janssen T, Lindemans M, Baggerman G, et al. Approaches to identify endogenous peptides in the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;615:29–47.

-

Laschuk A, Monteiro KM, Vidal NM, Pinto PM, Duran R, Cerveñanski C, et al. Proteomic survey of the cestode Mesocestoides corti during the first 24 hours of strobilar evolution. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:645–56.

-

Rai R, Singh N, Elesela South, Tiwari S, Rathaur S. MALDI mass sequencing and biochemical characterization of Setaria cervi protein tyrosine phosphatase. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:147–54.

-

Konop CJ, Knickelbine JJ, Sygulla MS, Vestling MM, Stretton AOW. Different neuropeptides are expressed in different functional subsets of cholinergic excitatory motorneurons in the nematode Ascaris suum. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6:855–lxx.

-

Marks NJ, Shaw C, Halton DW, Thompson DP, Geary TG, Li C, et al. Isolation and preliminary biological assessment of AADGAPLIRFamide and SVPGVLRFamide from Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:1170–six.

-

Konop CJ, Knickelbine JJ, Sygulla MS, Wruck CD, Vestling MM, Stretton AOW. Mass spectrometry of unmarried GABAergic somatic motorneurons identifies a novel inhibitory peptide, Equally-NLP-22, in the nematode Ascaris suum. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:2009–23.

-

Mádi A, Mikkat South, Ringel B, Thiesen HJ, Glocker MO. Profiling phase-dependent changes of poly peptide expression in Caenorhabditis elegans by mass spectrometric proteome analysis leads to the identification of stage-specific marker proteins. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:1809–17.

-

Yatsuda AP, Krijgsveld J, Cornelissen AWCA, Heck AJR, De Vries E. Comprehensive analysis of the secreted proteins of the parasite Haemonchus contortus reveals extensive sequence variation and differential immune recognition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16941–51.

-

Vepřek P, Ježek J, Velek J, Tallima H, Montash M, El Ridi R. Peptides and multiple antigen peptides from Schistosoma mansoni glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase: preparation, immunogenicity and immunoprotective capacity in C57BL/6 mice. J Pept Sci. 2004;10:350–62.

-

Gare D, Boyd J, Connolly B. Developmental regulation and secretion of nematode-specific cysteine-glycine domain proteins in Trichinella spiralis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;134:257–66.

-

Yew JY, Kutz KK, Dikler Southward, Messinger L, Li L, Stretton AO. Mass spectrometric map of neuropeptide expression in Ascaris suum. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488:396–413.

-

Quinn GAP, Heymans R, Rondaj F, Shaw C, de Jong-Brink K. Schistosoma mansoni dermaseptin-like peptide: structural and functional characterization. J Parasitol. 2005;91:1340–51.

-

Robinson MW, Gare DC, Connolly B. Profiling excretory/secretory proteins of Trichinella spiralis muscle larvae by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Vet Parasitol. 2005;132:37–41.

-

Loukas A, Hintz G, Linder D, Mullin NP, Parkinson J, Tetteh KKA, et al. A family of secreted mucins from the parasitic nematode Toxocara canis bears diverse mucin domains but shares similar flanking half dozen-cysteine echo motifs. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39600–7.

-

Yamauchi S, Higashitani N, Otani M, Higashitani A, Ogura T, Yamanaka M. Involvement of HMG-12 and CAR-ane in the cdc-48.one expression of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2008;318:348–59.

-

Monteiro KM, Zaha A, Ferreira HB. Recombinant subunits every bit tools for the structural and functional characterization of Echinococcus granulosus antigen B. Exp Parasitol. 2008;119:490–8.

-

Goldfinch GM, Smith WD, Imrie L, McLean 1000, Inglis NF, Pemberton AD. The proteome of gastric lymph in normal and nematode infected sheep. Proteomics. 2008;8:1909–18.

-

Ahmad R, Srivastava AK, Walter RD. Purification and biochemical characterization of cytosolic glutathione-Due south-transferase from filarial worms Setaria cervi. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;151:237–45.

-

Sahoo MK, Sisodia BS, Dixit S, Joseph SK, Gaur RL, Verma SK, et al. Immunization with inflammatory proteome of Brugia malayi adult worm induces a Th1/Th2-immune response and confers protection against the filarial infection. Vaccine. 2009;27:4263–71.

-

Yuan SS, Xing XM, Liu JJ, Huang QY, Yang SQ, Peng F. Screening and identification of differentially expressed proteins between woman and male person worms of Schistosoma japonicum. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;43:695–9.

-

Pak JH, Moon JH, Hwang SJ, Cho SH, Seo SB, Kim TS. Proteomic assay of differentially expressed proteins in human cholangiocarcinoma cells treated with Clonorchis sinensis excretory-secretory products. J Prison cell Biochem. 2009;108:1376–88.

-

Sanglas L, Aviles FX, Huber R, Gomis-Rüth FX, Arolas JL. Mammalian metallopeptidase inhibition at the defense barrier of Ascaris parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1743–7.

-

Yan F, Xu L, Liu L, Yan R, Vocal Ten, Li X. Immunoproteomic analysis of whole proteins from male and female adult Haemonchus contortus. Vet J. 2010;185:174–ix.

-

Jarecki JL, Andersen G, Konop CJ, Knickelbine JJ, Vestling MM, Stretton AO. Mapping neuropeptide expression by mass spectrometry in single dissected identified neurons from the dorsal ganglion of the nematode Ascaris suum. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:505–19.

-

Brophy PM, Jefferies JR. Proteomic identification of glutathione Southward-transferases from the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proteomics. 2001;1:1463–viii.

-

Kawasaki I, Jeong MH, Shim YH. Regulation of sperm-specific proteins by IFE-1, a germline-specific homolog of eIF4E, in C. elegans. Mol Cells. 2011;31:191–vii.

-

Clegg RA, Bowen LC, Bicknell AV, Tabish M, Prescott MC, Rees HH, et al. Characterisation of the N'ane isoform of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PK-A) catalytic subunit in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Curvation Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:38–45.

-

Millares P, LaCourse EJ, Perally South, Ward DA, Prescott MC, Hodgkinson JE, et al. Proteomic profiling and poly peptide identification by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in unsequenced parasitic nematodes. PLoS One. 2012;seven:e33590.

-

Ondrovics M, Silbermayr K, Mitreva M, Young ND, Razzazi-Fazeli Eastward, Gasser RB, et al. Proteomic analysis of Oesophagostomum dentatum (Nematoda) during larval transition, and the effects of hydrolase inhibitors on development. PLoS One. 2013;eight:e63955.

-

Tian F, Hou Grand, Chen 50, Gao Y, Zhang X, Ji M, et al. Proteomic analysis of schistosomiasis japonica vaccine candidate antigens recognized past UV-attenuated cercariae-immunized porcine serum IgG2. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:2791–803.

-

JebaMercy G, Durai S, Prithika U, Marudhupandiyan S, Dasauni P, Kundu S, et al. Role of DAF-21protein in Caenorhabditis elegans amnesty against Proteus mirabilis infection. J Proteom. 2016;145:81–90.

-

Henze A, Homann T, Rohn I, Aschner M, Link CD, Kleuser B, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system to study post-translational modifications of human transthyretin. Sci Rep. 2016;vi:37346.

-

Timm T, Grabitzki J, Severcan C, Muratoglu Southward, Ewald L, Yilmaz Y, et al. The PCome of Ascaris suum equally a model system for intestinal nematodes: identification of phosphorylcholine-substituted proteins and first characterization of the PC-epitope structures. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:1263–74.

-

Wang F, Xu L, Vocal X, Li X, Yan R. Identification of differentially expressed proteins between complimentary-living and activated third-stage larvae of Haemonchus contortus. Vet Parasitol. 2016;215:72–seven.

-

Mikeš L, Man P. Purification and label of a saccharide-binding protein from penetration glands of Diplostomum pseudospathaceum—a bifunctional molecule with cysteine protease activity. Parasitology. 2003;127:69–77.

-

Cheng G-F, Lin J-J, Feng X-G, Fu Z-Q, Jin Y-1000, Yuan C-X, et al. Proteomic assay of differentially expressed proteins between the male and female worm of Schistosoma japonicum afterwards pairing. Proteomics. 2005;v:511–21.

-

Robinson MW, Connolly B. Proteomic analysis of the excretory-secretory proteins of the Trichinella spiralis L1 larva, a nematode parasite of skeletal muscle. Proteomics. 2005;5:4525–32.

-

Ahn DH, Singaravelu G, Lee Southward, Ahnn J, Shim YH. Functional and phenotypic relevance of differentially expressed proteins in calcineurin mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proteomics. 2006;half dozen:1340–l.

-

Grabitzki J, Ahrend Thou, Schachter H, Geyer R, Lochnit G. The PCome of Caenorhabditis elegans as a prototypic model system for parasitic nematodes: identification of phosphorylcholine-substituted proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;161:101–eleven.

-

Acosta D, Cancela M, Piacenza L, Roche L, Carmona C, Tort JF. Fasciola hepatica leucine aminopeptidase, a promising candidate for vaccination against ruminant fasciolosis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;158:52–64.

-

Mádi A, Mikkat S, Koy C, Ringel B, Thiesen HJ, Glocker MO. Mass spectrometric proteome analysis suggests anaerobic shift in metabolism of Dauer larvae of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1763–70.

-

Wuhrer M, Grimm C, Dennis RD, Idris MA, Geyer R. The parasitic trematode Fasciola hepatica exhibits mammalian-type glycolipids also as Gal(Β1-vi)Gal-terminating glycolipids that account for cestode serological cross-reactivity. Glycobiology. 2004;14:115–26.

-

Mika A, Gołebiowski M, Szafranek J, Rokicki J, Stepnowski P. Identification of lipids in the cuticle of the parasitic nematode Anisakis simplex and the somatic tissues of the Atlantic cod Gadus morhua. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:334–twoscore.

-

Lochnit G, Nispel South, Dennis RD, Geyer R. Structural analysis and immunohistochemical localization of tow acidic glycosphingolipids from the porcine, parasitic nematode, Ascaris suum. Glycobiology. 1998;eight:891–ix.

-

Lochnit One thousand, Dennis RD, Ulmer AJ, Geyer R. Structural elucidation and monokine-inducing activity of two biologically active zwitterionie glycosphingolipids derived from the porcine parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:466–74.

-

Gerdt Due south, Dennis RD, Borgonie G, Schnabel R, Geyer R. Isolation, characterization and immunolocalization of phosphorylcholine-substituted glycolipids in developmental stages of Caenorhabditis elegans. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:952–63.

-

Wuhrer M, Rickhoff S, Dennis RD, Lochnit G, Soboslay PT, Baumeister Due south, et al. Phosphocholine-containing, zwitterionic glycosphingolipids of adult Onchocerca volvulus as highly conserved antigenic structures of parasitic nematodes. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt2):417–23.

-

Wuhrer 1000, Berkefeld C, Dennis RD, Idris MA, Geyer R. The liver flukes Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica express the leucocyte cluster of differentiation marking CD77 (globotriaosylceramide) in their tegument. Biol Chem. 2001;382:195–207.

-

López-Marín LM, Montrozier H, Lemassu A, García East, Segura E, Daffé Thousand. Structure and antigenicity of the major glycolipid from Taenia solium cysticerci. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;119:33–42.

-

Iriko H, Nakamura K, Kojima H, Iida-Tanaka Northward, Kasama T, Kawakami Y, et al. Chemical structures and immunolocalization of glycosphingolipids isolated from Diphyllobothrium hottai adult worms and plerocercoids. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:3549–59.

-

Wuhrer Thousand, Grimm C, Zähringer U, Dennis RD, Berkefeld CM, Idris MA, et al. A novel GlcNAcα1-HPO3-6Gal(1-1)ceramide antigen and alkylated inositol-phosphoglycerolipids expressed by the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. Glycobiology. 2003;13:129–37.

-

Friedl CH, Lochnit G, Zähringer U, Bahr U, Geyer R. Structural elucidation of zwitterionic carbohydrates derived from glycosphingolipids of the porcine parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. Biochem J. 2003;369:89–102.

-

Paschinger K, Rendić D, Lochnit G, Jantsch 5, Wilson IBH. Molecular basis of anti-horseradish peroxidase staining in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49588–98.

-

Paschinger One thousand, Wilson IBH. 2 types of galactosylated fucose motifs are present on N-glycans of Haemonchus contortus. Glycobiology. 2015;25:585–90.

-

Hewitson JP, Nguyen DL, van Diepen A, Smit CH, Koeleman CA, McSorley HJ, et al. Novel O-linked methylated glycan antigens decorate secreted immunodominant glycoproteins from the abdominal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46:157–seventy.

-

Veríssimo CM, Morassutti AL, von Itzstein M, Sutov M, Hartley-Tassell L, McAtamney Due south, et al. Characterization of the N-glycans of female Angiostrongylus cantonensis worms. Exp Parasitol. 2016;166:137–43.

-

Paschinger Thousand, Wilson IBH. Assay of zwitterionic and anionic Northward-linked glycans from invertebrates and protists by mass spectrometry. Glycoconj J. 2016;33:273–83.

-

Jiménez-Castells C, Vanbeselaere J, Kohlhuber S, Ruttkowski B, Joachim A, Paschinger K. Gender and developmental specific N-glycomes of the porcine parasite Oesophagostomum dentatum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1861:418–thirty.

-

Yan S, Wang H, Schachter H, Jin C, Wilson IBH, Paschinger Thou. Ablation of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases in Caenorhabditis induces expression of unusual intersected and bisected N-glycans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2018;1862:2191–203.

-

Yan Southward, Vanbeselaere J, Jin C, Blaukopf M, Wöls F, Wilson IBH, et al. Cadre richness of Due north-glycans of Caenorhabditis elegans: a case written report on chemical and enzymatic release. Anal Chem. 2018;ninety:928–35.

-

Cipollo JF, Awad AM, Costello CE, Hirschberg CB. N-glycans of Caenorhabditis elegans are specific to developmental stages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26063–72.

-

Robijn MLM, Koeleman CAM, Hokke CH, Deelder AM. Schistosoma mansoni eggs excrete specific free oligosaccharides that are detectable in the urine of the homo host. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;151:162–72.

-

Robijn MLM, Koeleman CAM, Wuhrer M, Royle 50, Geyer R, Dwek RA, et al. Targeted identification of a unique glycan epitope of Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens using a diagnostic antibiotic. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;151:148–61.

-

Kaneiwa T, Yamada S, Mizumoto Southward, Montaño AM, Mitani Due south, Sugahara Chiliad. Identification of a novel chondroitin hydrolase in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14971–9.

-

Tefsen B, van Stijn CMW, van den Broek M, Kalay H, Knol JC, Jimenez CR, et al. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of multivalent neoglycoconjugates conveying the helminth glycan antigen LDNF. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:1501–7.

-

Borloo J, De Graef J, Peelaers I, Nguyen DL, Mitreva Thou, Devreese B, et al. In-depth proteomic and glycomic analysis of the developed-stage Cooperia oncophora excretome/secretome. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:3900–11.

-

Parsons LM, Mizanur RM, Jankowska Due east, Hodgkin J, O'Rourke D, Stroud D, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans bacterial pathogen resistant bus-4 mutants produce contradistinct mucins. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107250.

-

Yan S, Jin C, Wilson IBH, Paschinger One thousand. Comparisons of Caenorhabditis fucosyltransferase mutants reveal a multiplicity of isomeric North-glycan structures. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:5291–305.

-

Alim MA, Fu Y, Wu Z, Zhao S, Cao J. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of cost-like receptors and association with Haemonchus contortus infection in goats. Pak Vet J. 2016;36:286–91.

-

Nagorny SA, Aleshukina AV, Aleshukina IS, Ermakova LA, Pshenichnaya NY. The awarding of proteomic methods (MALDI-toff MS) for studying protein profiles of some nematodes (Dirofilaria and Ascaris) for differentiating species. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;S1201–9712(19):30113–four.

-

Lyons E, Tolliver South, Drudge J. Historical perspective of cyathostomes: prevalence, treatment and command programs. Vet Parasitol. 1999;85:97–112.

-

Bredtmann CM, Krücken J, Murugaiyan J, Balard A, Hofer H, Kuzmina TA, et al. Concurrent proteomic fingerprinting and molecular assay of cyathostomins. Proteomics. 2019;19:e1800290.

-

To G, Maldi E, Table LT, Fume V, Eppendorf One thousand, Belittling R, et al. Generating new MSP with Bruker Microflex LT. https://spectra.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/spectra/. Accessed 14 May 2019.

-

Yajima F, Kurono Y, Igarashi Thou, Uchida A, Ozeki Y. On the unknown nematoda eggs found in human stool which are confusing with the egg of human parasites. J Jpn Assoc Rural Med. 1959;8:57–61.

-

Bradbury RS, Speare R. Passage of Meloidogyne eggs in human stool: forgotten, but not gone. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1458–9.

-

Santos FLN, de Souza AMGC, Dantas-Torres F. Meloidogyne eggs in human being stool in Northeastern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016;49:802.

-

Utzinger J, Becker SL, Knopp S, Blum J, Neumayr AL, Keiser J, et al. Neglected tropical diseases: diagnosis, clinical management, treatment and control. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13727.

-

Becker SL, Liwanag HJ, Snyder JS, Akogun O, Belizario 5, Freeman MC, et al. Toward the 2020 goal of soil-transmitted helminthiasis command and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006606.

-

van Lieshout L, Roestenberg M. Clinical consequences of new diagnostic tools for intestinal parasites. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:520–8.

-

González LM, Montero Due east, Harrison LJS, Parkhouse RME, Garate T. Differential diagnosis of Taenia saginata and Taenia solium infection past PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:737–44.

-

Flisser A, Viniegra A-Due east, Aguilar-Vega 50, Garza-Rodriguez A, Maravilla P, Avila G. Portrait of human being tapeworms. J Parasitol. 2004;90:914–vi.

-

Mayta H, Gilman RH, Prendergast E, Castillo JP, Tinoco YO, Garcia HH, et al. Nested PCR for specific diagnosis of Taenia solium taeniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:286–9.

-

Mayta H, Talley A, Gilman RH, Jimenez J, Verastegui 1000, Ruiz K, et al. Differentiating Taenia solium and Taenia saginata infections by simple hematoxylin-eosin staining and PCR-restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:133–7.

-

Boissier J, Grech-Angelini S, Webster BL, Allienne JF, Huyse T, Mas-Coma S, et al. Outbreak of urogenital schistosomiasis in Corsica (France): an epidemiological instance report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:971–ix.

-

Klopfleisch R, Weiss ATA, Gruber AD. Excavation of a buried treasure—Dna, mRNA, miRNA and protein assay in formalin fixed, alkane series embedded tissues. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:797–810.

-

Lehmann U, Kreipe H. Real-time PCR analysis of Deoxyribonucleic acid and RNA extracted from formalin-fixed and methane series-embedded biopsies. Methods. 2001;25:409–eighteen.

-

Bonin South. PCR analysis in archival postmortem tissues. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:184–six.

-

Laroche Thousand, Bérenger JM, Gazelle G, Blanchet D, Raoult D, Parola P. Corrigendum: MALDI-TOF MS protein profiling for the rapid identification of chagas disease triatomine vectors and application to the triatomine creature of French Guiana. Parasitology. 2018;145:676.

-

Neuschlova Thousand, Vladarova M, Kompanikova J, Sadlonova V, Novakova Eastward. Identification of Mycobacterium species by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1021:37–42.

-

Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. Identification of molds by matrix-assisted light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:369–79.

-

Lagace-Wiens PRS, Adam HJ, Karlowsky JA, Nichol KA, Pang PF, Guenther J, et al. Identification of claret culture isolates direct from positive blood cultures by utilise of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-fourth dimension of flying mass spectrometry and a commercial extraction organisation: assay of performance, price, and turnaround time. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;fifty:3324–8.

-

Huang B, Zhang L, Zhang Westward, Liao Chiliad, Zhang S, Zhang Z, et al. Direct detection and identification of bacterial pathogens from urine with optimized specimen processing and enhanced testing algorithm. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1488–95.

-

Steel C, Golden A, Kubofcik J, LaRue N, De los Santos T, Domingo GJ, et al. Rapid Wuchereria bancrofti-specific antigen Wb123-based IgG4 immunoassays as tools for surveillance post-obit mass drug assistants programs on lymphatic filariasis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;xx:1155–61.

-

Sparbier Thousand, Wenzel T, Dihazi H, Blaschke South, Müller GA, Deelder A, et al. Immuno-MALDI-TOF MS: new perspectives for clinical applications of mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2009;9:1442–fifty.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This systematic review received financial support from the 'Landesforschungsförderprogramm des Saarlandes'.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

MF conducted the systematic review of the literature and extracted data. MF and SLB independently assessed published manufactures for eligibility, analysed and discussed data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. SP and JU contributed to data estimation and revised the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1.

Search strategies employed for our systematic review pertaining to the awarding of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a diagnostic tool in man and veterinarian helminthology.

Additional file 2.

PRISMA checklist for a systematic review examining the application of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry equally potential tool in diagnostic human and veterinary helminthology.

Additional file 3.

List of references included in the terminal review (n = 84 manufactures).

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/aught/one.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Feucherolles, 1000., Poppert, S., Utzinger, J. et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry every bit a diagnostic tool in human and veterinary helminthology: a systematic review. Parasites Vectors 12, 245 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3493-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3493-9

Keywords

- Diagnosis

- Helminths

- MALDI-TOF

- Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Parasites

Source: https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-019-3493-9

0 Response to "Maldi Method to Characterize a Specific Protein Reviews"

Post a Comment